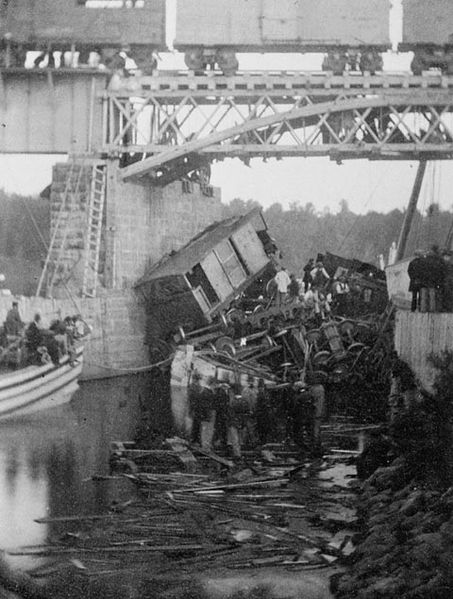

THE BELOEIL BRIDGE DISASTER

The bridge over the Richelieu River, between Beloeil and St. Hilaire, was the scene of Canada’s worst railway accident. On June 29, 1864, a train left Pointe Levis ( opposite Quebec ) carrying 354 immigrants – German, Australian and Norwegian – who had just arrived from Bremen on the ship »Neckar ». Hauled by locomotive No. 168, the »Ham », built in 1857 by D. C. Gunn of Hamilton, the train consisted of 5 immigrant cars, 5 coaches, and a brake van. The immigrant cars were really box cars with a platform, a few windows, and removable benches; and were used when needed to carry immigrants westward at very low fares. At other times they were used as freight cars.

Engineer William Burnley ran the train from Pointe Levis to Richmond, where he expected to be relieved, but there was a party in town that night and a full crew could not be found. Burnley had had seven years experience in engine service on the Quebec and Richmond Railway, but he did not know the road between Richmond and Montreal. He did not want to proceed, but unfortunately was persuaded to do so by the locomotive foreman at Richmond. The train set out shortly before midnight with the incomplete crew consisting of Engineer Burnley, Conductor Thomas Finn, one brakeman named Giroux, and an unknown fireman.

Approaching the Beloeil Bridge from the east, the railway ran parallel to the river down a sharp grade through dense woods which prevented a clear view of the bridge; the line then curved sharply to the right onto the bridge. On the opposite ( Beloeil ) side, there was a swing span and the only signal at the time was a lantern showing red or white on the swing span itself. Because of the thick woods and the curve, the signal could not be seen when approached from the east until the train was almost on the bridge. Legally the boats had the right-of-way and trains were required to come to a full stop – then approach the span under full control. Generally, however, the steamboats conceded the right-of-way to regular trains, and the train crews had become careless, and recklessly ignored the mandatory stop.

What really happened will never be known. But probably because Burnley did not know the road, the train got out of control coming from the hill. When he saw the red light, he whistled for brakes, but it was too late. The brakeman, who should have been standing by was otherwise engaged. The side-wheel tug »Champlain » with six barges in tow, was passing through the draw, and the train tumbled out of the end of the span and crashed down on one of the barges, only the last coach remaining on the bridge.

The Conductor, brakeman, fireman and 97 passengers were killed and about 200 were injured. Burnley survived the crash, and was immediately arrested for manslaughter, although subsequently he was acquitted because it was thought that the Company was more to blame.. However, he was broken mentally and physically and for years wandered around Montreal, known to all as the engineer in the Beloeil Bridge Disaster.

At Acton Vale, between St. Hyacinthe and Richmond, there was a large copper mine, owned for many years by Jefferson Davis, later President of the Confederate States, and while fighting a forest fire, the employees of the mine saved a large quantity of firewood belonging to the Grand Trunk Railway. As a reward, the railway gave the people of Acton Vale a free excursion to the picnic ground at Otterburn Park, near Beloeil. They came up on the night train from Portland, and, arriving at the bridge about 7:00 a.m. they were horrified to see the draw filled with splintered wreckage, and a few farmers carrying the dead and injured to the bank of the river. Among those from Acton Vale was Dr. Mount, a noted physician, and his 13 year old daughter, who frequently assisted him as an amateur nurse. They immediately set about relieving the injured. Sixty-five years later, the daughter, Mrs. Mount-Duckett, was a valued member of the Canadian Railroad Historical Association, and recalled in vivid detail the harrowing scenes at the Beloeil Bridge disaster.

One more life was claimed two years later when a man on a passing train, wishing to see the wreckage in the river below, stood on the bottom stop of a car and leaned far out. The telegraph wires were strung more loosely in those days with a very pronounced curve of catenary, and were too close to the side of the train. So the speed of the train and the sharp upward slope of the wire sliced the man’s head off as neatly as a guillotine.

by Douglas Brown.

Source: Canadian Railroad Historical Association Inc. Montreal, Que. – October 1954

Tous droits réservés au Musée Saint-Éphrem